Credit_UoS_A Hutchings

New research by a team of scientists, including PhD student Jeremy Lockwood from the Natural History Museum, has identified the remains of one of Europe’s largest ever land-based hunter, a dinosaur that measured over 10m long and lived around 125 million years ago.

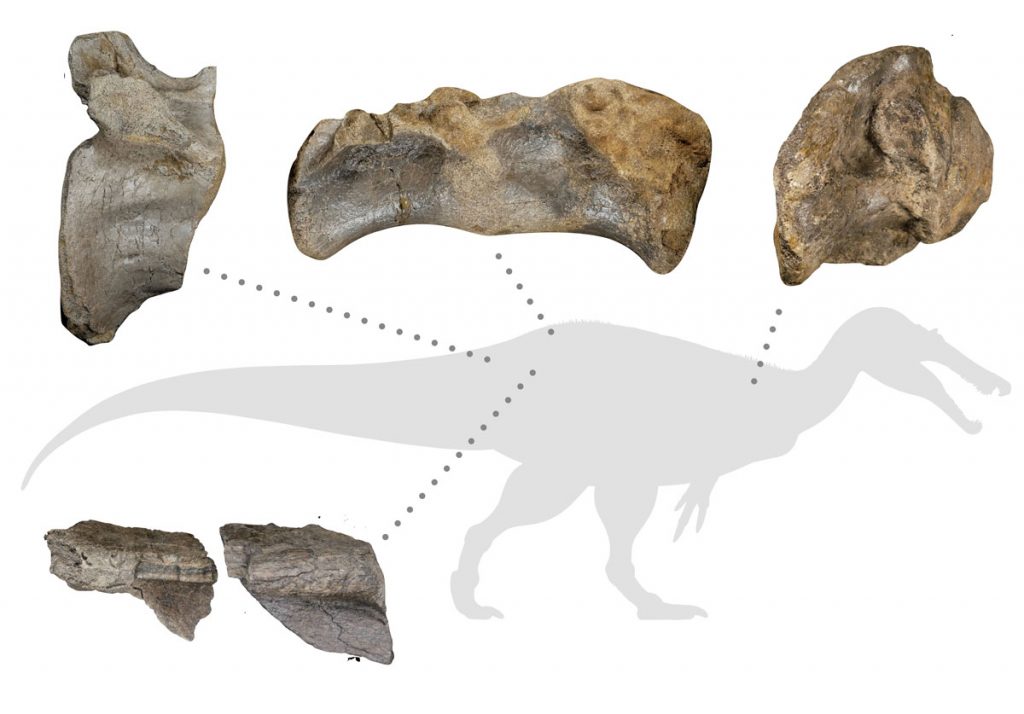

The remains comprising of several bones uncovered on the Isle of Wight, on the south coast of England, and now housed at Dinosaur Isle Museum in Sandown, belonged to a type of two-legged, crocodile-faced predatory dinosaur known as spinosaurids. Dubbed the ‘White Rock spinosaurid’ after the geological layer in which it was found.

Chris Barker, PhD student, University of Southampton, who led the study said, ‘This was a huge animal, exceeding 10m in length and probably several tonnes in weight. Judging from some of the dimensions, it appears to represent one of the largest (if not the largest) predatory dinosaur ever found in Europe.

‘It’s a shame it’s only known from a small amount of material, but these are enough to show it was an immense creature.’

The discovery follows previous work on spinosaurids by the Natural History Musuem, London, and the University of Southampton, revealing two new species in 2021.

The bones of the ‘White Rock spinosaurid’, which include huge pelvic and tail vertebrae, amongst other pieces, were discovered near Compton Chine, on the southwest coast of the Isle of Wight. The Cretaceous rocks are famous for their dinosaurs, but little appreciated is the fact that the Island’s fossil record preserves dinosaurs from more than one section of history.

The bones of the ‘White Rock spinosaurid’, which include huge pelvic and tail vertebrae, amongst other pieces, were discovered near Compton Chine, on the southwest coast of the Isle of Wight. The Cretaceous rocks are famous for their dinosaurs, but little appreciated is the fact that the Island’s fossil record preserves dinosaurs from more than one section of history.

The 125 million year old Vectis Formation preserves the beginning of a period of rising sea levels, where the ‘White Rock spinosaurid’ stalked lagoonal waters and sandflats in search of food.

Because the animal is so far only known from fragments it has not yet been given a formal scientific name. The team hope that in time more remains will be discovered. This new discovery, however, continues to strengthen the argument that spinosaurid dinosaurs originated and diversified in western Europe before becoming more widespread.

Marks on the bone also showed how, even after death, the body of this giant probably supported a range of scavengers and decomposers.

Jeremy Lockwood, a PhD student at Natural History Museum and the University of Portsmouth added, ‘Most of these amazing fossils were found by Nick Chase, one of Britain’s most skilled dinosaur hunters, who sadly died just before the Covid epidemic.

‘I was searching for remains of this dinosaur with Nick and found a lump of pelvis with tunnels bored into it, each about the size of my index finger. We think they were caused by bone eating larvae of a type of scavenging beetle. It’s an interesting thought that this giant killer wound up becoming a meal for a host of insects.’

The researchers hope to generate thin sections of the material to look at the microscopic internal properties of the bones in the near future, which may provide information about its growth rate and possible age.

The paper A European giant: a large spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Vectis Formation (Wealden Group, Early Cretaceous) UK is published in the journal PeerJ.